Articles

Samathua Kalvi for All: Making Low-Fee Schools Part of the Solution

November 7, 2025

Degrees That Don’t Pay: Is Theory Without Skills Failing Our Youth?

November 11, 2025Kochi Water Crisis: Urban Growth Amid a Deepening Water Shortage

Access to safe drinking water is becoming increasingly difficult in Kochi due to a lack of planning, accountability, and inadequate infrastructure.

Despite receiving 2,810 mm of rainfall, the city of Kochi struggles to convert natural abundance into a reliable supply. According to Kerala Water Authority (KWA), Kochi water supply faces a shortage of 80 million litres daily (MLD). Places like Edappally, Vennala, Cheranalloor, Vaduthala, and Vypeen already face acute water shortages. There is a severe Kochi water crisis.

Over 55,000 households lack piped water, and none of the 19,357 slum households have a tap water connection, according to data in the City Water Balance Plan (CWBP) 2022. They depend on tankers and public taps for a few buckets of water. Quality of water adds to the crisis, with 86% of groundwater and 71% of tap water samples across 74 wards failing the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) for drinking water (KSCSTE-CWRDM 2019).

Kochi wasn’t always this way. It’s a city built on water, surrounded by rivers, fed by the rain, and with a backwaters-linked livelihood. However, over the course of two decades, the city has expanded rapidly— apartments, tech parks, malls, etc. A CUSAT-SACON-FLAME study reveals that built-up areas in Kochi have increased by 126% between 2001 and 2020, far above the global average of 20%. Yet water systems remain unchanged.

Who’s in Charge of Water in Kochi?

Kochi’s water woes are not just about pipes and pumps but about people, policies, and urban planning. The responsibilities are scattered across multiple agencies:

- KWA manages water production and distribution

- Kochi Municipal Corporation (KMC) issues building permits and oversees sanitation

- State departments fund infrastructure projects

These agencies operate in silos, without integrated planning, data sharing, or a transparent system of accountability. For instance, KMC approves new building construction in areas lacking an adequate water supply without consulting KWA. Thus, unchecked urban growth continues without corresponding water security planning.

To start with, KWA still relies on two water treatment plants (WTP) at Aluva and Maradu, together supplying ~200–210 MLD to KMC, while demand is projected at 238 MLD by 2025 (CWBP 2022). In 2021-22, households received only 102.6 MLD, leaving a shortfall of 135 MLD compared to the projected water demands, driving households to groundwater.

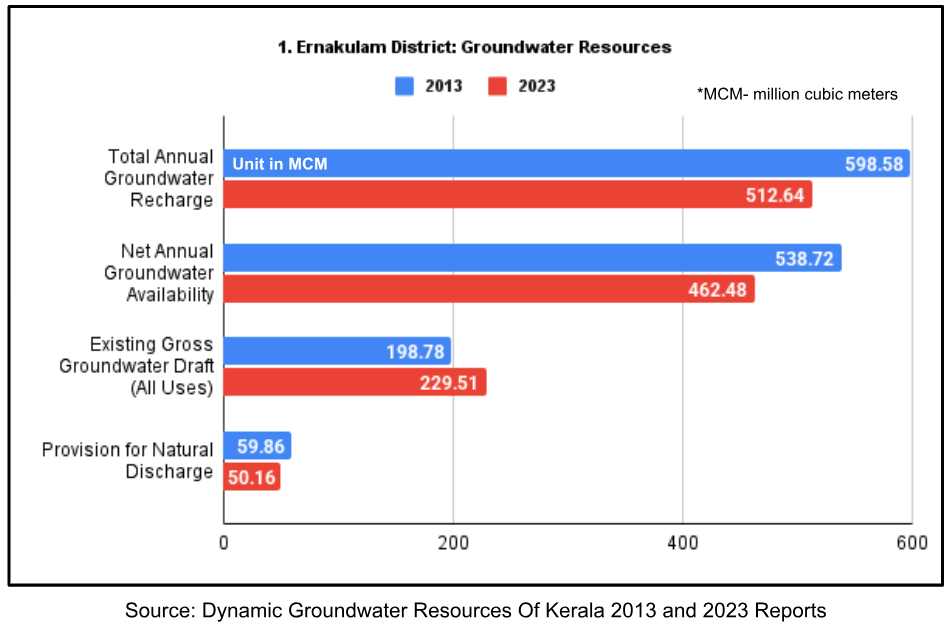

Groundwater, once a buffer, is also depleting. In Ernakulam, net annual availability (total volume available for extraction) declined from 538.72 million cubic metres (MCM) in 2013 to 462.48 MCM in 2023 (Table 1). This drop was compounded by over-extraction by housing complexes and commercial units.

The Kerala Municipality Building Rules (KMBR 2019) mandate Rainwater Harvesting System (RWH) in new buildings to enable groundwater recharging. But in practice, many buildings skip it or install token systems. The Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) 2016 scheme had earmarked 1 crore for setting RWH systems on the rooftop of 1200 houses in the city. But the project failed due to implementation issues and limited public interest.

The burden on groundwater can be reduced by greywater recycling, which involves reusing water from sinks, baths, or kitchens for flushing or irrigation. But Kochi recycles zero MLD of greywater (CWBP 2022). The city generates over 138 MLD of sewage, but treats just 3.25 MLD, while the rest pollutes rivers, canals, and the groundwater.

The Human Cost of the Kochi Water Crisis

For women and children, water scarcity means hours spent fetching water, missed educational and economic opportunities, and loss of dignity. In the slum areas, not having private taps leads to illegal and unsafe makeshift connections or reliance on polluted sources, heightening health risks. Poor sanitation and untreated sewage create fertile ground for waterborne diseases like cholera, diarrhoea, and typhoid, burdening healthcare systems.

As the city expands, the informal dependence on tanker trucks supplying potable water will add to households’ costs. The impact is already visible since January this year; the water transporters have doubled the tariffs in Ernakulam. A 5,000-litre tanker that cost ₹650 in 2018 now costs ~₹1,500.

All this threatens ecological sustainability, especially in coastal wards where saline intrusion is already a risk. In sum, water is the foundation of health, education, livelihood, and human dignity; if not addressed, it will degrade the overall quality of life.

Fixing the Flow: What Can Be Done?

The Kochi water crisis requires more investments and coherence amongst existing mechanisms across institutions and actors.

Strengthen Governance and Regulations

It needs to start with an Integrated Urban Water Cell to unify KWA, KMC, and state departments for coordinated planning, data sharing, and joint accountability. Third-party RWH audits with penalties must be enforced. Chennai serves as a model. After making RWH mandatory in 2003, groundwater levels in Chennai rose 4.2 metres by 2006.

Promote Greywater Recycling and Technological Transparency

Kochi can learn from Bengaluru that mandates dual plumbing, where there are two pipe networks—a potable-drinking water pipe used only where necessary, and a non-potable, recycled water pipe which serves secondary needs—in new apartments. Installing real-time water quality monitoring stations with public dashboards and IoT-based smart sensors to keep track of groundwater levels, as seen in Bangalore’s Smart City program, can build transparency and trust.

Encourage Community Participation

NGOs can launch public awareness and school-level campaigns to engage the community. Kochi can adopt from Chennai’s “Water Warriors” campaign #RehydrateChennai, where residents showcased their functional RWH systems on social media, while the authorities inspected and recognised well-maintained structures. Such models, combined with policy tools like providing rebates for recharge, borewell metering, and conservation ratings, can boost adoption.

Fast-Track Ongoing Projects

Kerala’s Urban Water Services Improvement Programme, with SUEZ, aims to deliver 24/7 pressurized supply to 7 lakh residents, offering much-needed relief. Local initiatives like Kalamassery’s ₹25.55 crore pond and well revival in its 2025–26 budget show promise and must be scaled.

Conclusion

With urbanisation, population growth, and the proliferation of high-rise residential buildings, water demand in Kochi city is projected at 405 MLD by 2046 (KSCSTE-CWRDM 2019), indicating that the current policies lack urgency. The city must integrate systems, invest in resilience, and avoid borrowing survival lessons from the collapse faced by Delhi and Bengaluru. Water is more than a utility; it is a right and a measure of how a city values its people and future.

A city surrounded by water shouldn’t be thirsty. Kochi must act before abundance becomes absence.

Dr Sruthi Salunkhe is an alumna of CPPR Academy’s Public Policy Summer Bootcamp 2025 batch. She was mentored by Ms Meenuka Mathew, Fellow (Programme Design & Evaluation) at CPPR.

Views expressed by the authors are personal and need not reflect or represent the views of the Centre for Public Policy Research (CPPR).

Dr Shruti Salunkhe

Dr Shruti Babasaheb Salunkhe is a development management professional with work experience across national and international public health and governance programs, integrating policy research, stakeholder engagement, and program design to inform data-based policy decisions. After completing her Bachelor of Dental Surgery, she dedicated four years to preparing for the Civil Services Examination, which deepened her understanding of governance and public systems, sparking her interest in policy research.

She later pursued the Postgraduate Program in Development Management at ISDM to transition into the social sector and policy space. She is currently pursuing a Diploma in Governance and Government Studies from the Indian Institute of Governance and Leadership (IIGL) and volunteers with The ClimAct Initiative.