Articles

Debate surrounds Thiruvananthapuram metro: Is the project efficient?

May 16, 2024

CPPR DecodingthePolls Ep.29 | Analysing India’s 2024 Elections Amidst the Ongoing Polling

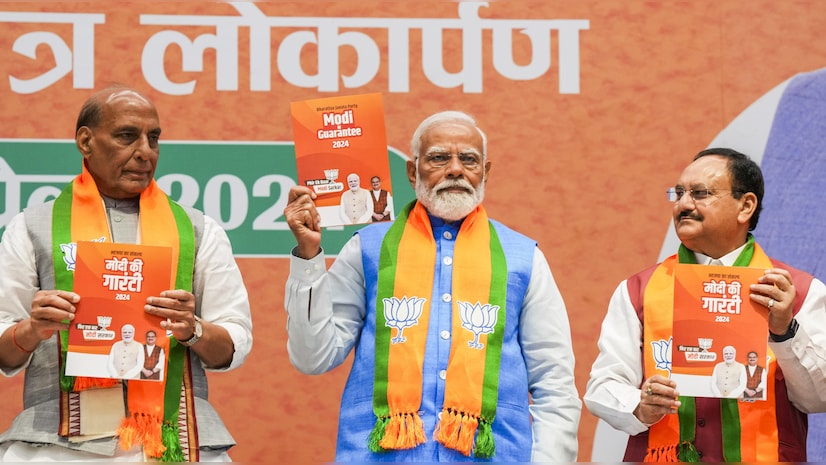

May 20, 2024BJP Manifesto 2024 Lacks Major Structural Reforms

The major political parties’ election manifesto provides their approach, thinking, and understanding of the current issues and challenges faced by the economy, society, and geopolitical nexus with national and international scenarios. However, what is apparently missing from both the Congress and BJP election manifestos are the intentions to address the long overdue structural reforms, which are embedded with institutional reforms and have huge potential for positive impacts on the economy, society, and welfare of the people. Most election manifestos’ promises are designed as deceptive ploys for perception changes among voters in general and targeted segments in particular.

Bharatiya Janata Party’s 76-page manifesto for the 2024 general elections broadly outlines its intention for the continuity and expansion of its several welfare initiatives of the last decade. The party’s manifesto focuses on key segments like rural areas, youth, farmers, women, and the middle class. The party counters last decade’s performance with that of the decade before 2014, wherein the country faced corruption, policy paralysis, and governance failures by the government of those times. In these fierce debates, there is not much the Congress party can defend itself with since its weaknesses are at multiple levels, from organisational to leadership at national and regional levels. Unlike the Congress Party manifesto, the BJP has largely avoided any upfront freebie announcements in their manifesto.

Nevertheless, there is a huge contrast in terms of aspirations of the segments vs the facilities and services available at present for these segments. However, evaluating each of the initiatives of the BJP is inevitable because ascertaining the long-term impacts created has to be done independently. The party might have touched every other aspect of society and the economy, but the institutionalisation of some of the aspects, like decentralisation and empowering the local bodies, especially the urban local bodies, the party, or the government, has not done much yet. Inadequate institutional reforms lead to a lack of accountability, causing delays and resource wastage year after year for quite a long time.

Given the mixed performance in urban and city development initiatives over the last decade, the BJP’s promises to shift the urban landscape towards providing world-class infrastructure and promoting sustainable living are ambitious undertakings. Accomplishing these goals within five years is no small feat and would require significant efforts from the government machinery, particularly in addressing the existing challenges within the local urban governance structure. These challenges include bureaucratic hurdles, rent-seeking practices, inadequate efforts to engage urban communities, a lack of independent evaluations, and the underutilization of technological tools in service delivery. It appears that the BJP’s election manifesto was crafted by individuals or a team with ambitious goals, possibly overlooking the complexities and obstacles inherent in achieving such sweeping changes within the specified timeframe.

Despite these challenges, the BJP has promised the following sweeping announcements made in the manifesto, which are impossible to achieve in a matter of few years without decentralisation and institutional reforms for cities’ overall governance systems:

- “Creation of new satellite townships near metro cities across India through a combination of reforms and policy initiatives.

- Create unified metropolitan transport systems that integrate multi-modal transport facilities and reduce commute time in cities.

- Create water-secure cities, leveraging best practices for wastewater treatment, aquifer recharge, and smart metering for bulk consumers.

- Long-term infrastructure projects with centre-state-city partnerships with a vision to revitalise our urban landscapes and enhance the quality of life for our citizens.

- Develop more green spaces like parks, playgrounds, etc., reviving water bodies and developing natural spaces to make cities more adaptable, sustainable, and people-friendly.

- Continue eliminating open landfills to manage all kinds of waste being produced in Bharat through ‘The Waste to Wealth Mission’.

- Undertake the creation of the Digital Urban Land Records System.

- Work with state governments and cities to encourage them to create a modern set of legislation, by-laws, and urban planning processes using technology.”

The central government has to initiate a vibrant public policy dialogue with state governments and local governments for effective implementation of each of the above aspects of bringing about transformational changes in the urban landscape. Moreover, without institutional and decentralised reforms to empower the urban local bodies to deliver social, physical and digital infrastructure, the BJP’s following promises would end up in a nightmare in years to come:

- “We have initiated metro in 20+ cities over the past decade; we will expand the metro network in major urban centres, ensuring last mile connectivity…We will construct ring roads around major cities to improve mobility and decongest cities…effective use of PM Gatishakti National Master Plan.

- We will undertake the creation of the Digital Urban Land Records System.

- We will work with state governments and cities to encourage them to create a modern set of legislation, by-laws and urban planning processes using technology.”

However, the BJP party manifesto assures that “we will undertake more institutional reforms and simplify processes using technology to ensure that citizen-government interaction is significantly improved,” but it is not all that easy to do urban governance reforms without learning from the past. Any government, whether central, state or local, has to first recognise the facts of what went wrong for all these years in terms of the inadequate delivery of services and facilities that the people have demanded and the rise of aspirations.

Also, it is strange that even after a quarter century, the major political parties are not openly advocating implementing the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments in true letter and spirit on not just the funds and functions but reasonable administrative and execution autonomy.

The BJP’s promises should have been more substantive on concrete steps for decentralisation and institutional reforms rather than the currently proposed several bunch of guarantees with overambitious minimum governance guarantees at the local body level. The party has promised to “take further steps to facilitate the fiscal autonomy and sustainability of Panchayati Raj Institutions.” While these institutions are already distanced from the people and local community, any attempt to bridge the gaps in local body governance and people’s expectations has to do with building confidence among people by addressing their immediate and long-term aspirations.

Regardless of which national party is elected to govern and the nature of governance at the state level across the country, establishing a smooth ecosystem to enhance local bodies is challenging without substantial reforms in decentralisation and institutional structure. Indeed, only a few states have established state-level finance commissions, which are crucial for improving governance at the local level. Therefore, the BJP’s promises may prove difficult to fulfil effectively concerning urban local bodies in the coming years. Will they walk the talk? Only time will tell us.

Views expressed by the author are personal and need not reflect or represent the views of the Centre for Public Policy Research.

Chandrasekaran Balakrishnan is Research Fellow (Urban Eco-system and Skill Development) with CPPR. His areas of research interest are economics of education, vocational education and skills development, economic reforms, liberal vision for India, water management, regional development, and city development. Chandrasekaran has an MA in Economics (University of Madras) and an MPhil in Social Sciences (Devi Ahilya Vishwavidyalaya University, Indore).