Articles

Leveraging AI in the Fight against COVID-19

April 28, 2020

The WHO’s Failures Are a Red Herring. A 2005 Pact Is the Real Problem

May 3, 2020Inward remittances and the upcoming crisis

Pessimism and uncertainty looms as India is going to face a reverse migration as a result of the global economic fallout triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, the article looks at the history, trends in migration and inward remittances to India, and puts forward a few options that might help rejuvenate the economy.

Nila Nair

From the time indentured labourers were sent to Britain during the colonial rule and after the great partition, India has had a long relationship with migration. Today, Indian diaspora is the largest in the world, spread over more than 110 countries. There are 30 million Indians overseas and India was the top recipient of remittances in 2018 with US$ 79 billion inward remittance. These millions of people sending billions of dollars as remittances to their families have helped the developing countries including India as it has become an unavoidable source of their well-being and the national income.

Trends in Migration and Remittances to India

The leading states in India for migration are Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Andhra Pradesh. These states account for more than 80 per cent of India’s total remittances, with Kerala having the highest i.e., 19 per cent. Uttar Pradesh has the most number of migrants followed by Bihar. The increase in migration from these states, which has now surpassed other progressive states like Kerala and Karnataka, can be a result of the sudden surge in their population and increase in the demand for work. The current population of migrants in select countries is given below.

Undoubtedly, the UAE has the largest share of migrants from India, followed by Saudi Arabia. India’s relationship with the UAE and the Gulf countries goes long back and the flow of migration from Kerala to these countries during the 1970s and 80s leading to the “Gulf Boom” has strengthened it. Kerala’s economy is particularly dependent on foreign remittances and has been in the forefront of the State’s economic growth. In 2003, remittances were 1.74 per cent higher than the State revenue receipts. Remittances from abroad have proved a better source for the poor than any foreign aids or investments as they directly receive cash for their daily expenses and provide protection against emergencies. Before the Gulf Boom, Kerala was known for its paradoxical state of being with high human development but a low economic growth. This has changed from the 1980s as a result of a large inflow of remittances and economic reforms. It is also argued that the per capita income of Kerala is much higher than the national average mainly because of the remittance flow.

While Indian economy as a whole is not dependent on remittances from abroad, states like Kerala and Punjab are among the most remittance-dependent economies in the world. The migration from Punjab focused on the developed western countries, especially Canada; whereas Kerala was an important labour supplier to the Middle East. Kerala and Punjab show a contradictory pattern of migration. Migration from Kerala tends to be for a limited period with high remittances; whereas for Punjab, most of the people who migrate want to be settled abroad and they do not send home money in the same manner as Kerala. A permanent family migration through the process of chain migration, especially in the case of the Jat Sikhs, has traditionally been the way of Punjab; while about 90 per cent of migrants from Kerala went to the Gulf countries to provide temporary labour.

The construction, manufacturing and retail sectors represent 85 per cent of the unskilled and semi-skilled labour migrants from India, while the rest are focused on healthcare, domestic and unclassified workers. Majority of the migrants from the states of Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Bihar and Rajasthan are unskilled and work in the construction and retail industries. Their jobs include masonry, carpentry, delivery services, retail clerks, etc. A large portion of the migrants from Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Telangana and Kerala constitutes semi-skilled workers employed in the healthcare, retail and manufacturing sectors. Skilled workers from states like Maharashtra and Karnataka, on the other hand, work in the IT sector overseas. The mass migration from India constituted majorly of unskilled and semi-skilled workers for a long time until the IT sector boom in the 1990s. Indian migration to the United States doubled during this time with the use of H1-B visas. Even in Gulf countries, a new class of highly skilled professional Indian workers are increasing today.

According to the World Bank, 82 per cent of the households in India received remittances in cash, 15 per cent as cheques or draft and 2 per cent as money orders. RBI suggests that more than half of such remittances are utilised for family maintenance, 20 per cent as bank deposits and 7 per cent for securing land, property, securities, etc. A study conducted by Grant Thornton has found that in states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, 25 per cent of the remittance received is used for debt repayment after household consumption. In Orissa, 11 per cent is used for marriages and in the North-east states and Jammu and Kashmir, 55 per cent of the remittance is used for the purpose of education. Goa, on the other hand, uses 39 per cent of the remittance for savings and investment activities. Thus, the diversity that makes the country unite can also be seen in the migration and remittance trend of different states.

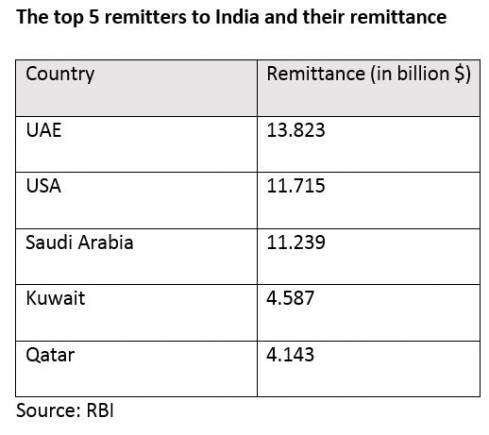

The UAE was the top remitter to India for the past few years followed by the USA. The Gulf countries together contribute more than half of the remittance to the country. India experienced a surge in the flow of remittance after the liberalisation policy of 1991, widely known as India’s second independence. This accelerated the integration of India into the world economy opening up vibrant opportunities and jobs abroad. The new economic policy coupled with the establishment of the market exchange rate in 1993 reduced the appeal of sending money through hawala networks. From this point, private transfers and remittances became an important constituent of India’s Balance of Payments and since the 1990s, Indians working overseas have been the world’s top remitters consistently. Until recently, remittances to India have proven to be one of the most stable forms of economic flows to the country.

The “Great Homecoming” and the Path Forward

The looming global financial crisis in light of the COVID-19 pandemic has already affected the world with the start of a recession. The great lockdown adding to the economic crisis at hand has stranded lakhs of migrants in more than 100 countries worldwide. The Department of Non-Resident Keralites (NoRKs) has already commenced online registration for people stranded abroad due to the ban on international flights. More than 3.4 lakh have already registered within days of its commencement. Majority of the migrant labourers, especially those in the unskilled and semi-skilled sector, will be rendered jobless. The “great homecoming” of these migrants will adversely affect the economy as unemployment will increase and the economically vulnerable will be pushed into poverty. The World Bank President David Malpass has stated that the recession will take a severe toll on the ability of migrants to send money home and the remittance to India will witness a sharp decline of 23 per cent to US $ 64 billion in this year. Economies dependent on remittances like Kerala will have to face a huge drought in its income as lakhs of migrants are waiting to return home. The internal migrants in the country might face a larger unemployment crisis as they will be returning back to their home states. At the same time, pessimism and uncertainty are looming over the market and will continue to be so for quite some time.

What can be done to help the situation? The most important task at hand is to handle the reverse migration in the country. The returning migrants will be more skilled in terms of their work experience abroad and therefore harnessing their potential can prove to be beneficial for the economy. Along with the registrations to return back to the country, websites can be equipped for profiling the migrants and reviewing their skillsets and past jobs. This portal can be used by private employers in the country and also by the government to mobilise potential job opportunities for the returnees. Most of the unskilled and semi-skilled migrant workers will be returning to their home states like Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Kerala, etc. The extent of return migration will be different for different states. States like Kerala, where the interstate migrants have dominated unskilled and semi-skilled markets until recently, witnessed a mass exodus of these migrants to their homeland, creating a shortage of workforce in the host state. The overseas returnees can marginally fill this gap. They can also be incentivised in forming self-help groups (SHGs) to find jobs and pool resources. They can also be encouraged to start small-scale businesses and enterprises of their choice.

In order to recover, the government must invest in projects that create more employment, such as an expansionary fiscal policy with increased government spending. Demand revival will be yet another crucial step in this process and for the demand to be improved, people should have sufficient disposable income. Thus, easing the tax liabilities, providing unemployment allowance for poor labourers, strengthening policies like MGNREGA, providing moratorium for repayment of loans and lending to MSMEs will be vital to rejuvenate the economy. The history of migration and remittance to India are taking a huge turn here. The repercussions of this economic pandemic will take a heavy toll on millions of lives unless there is quick and effective actions from both the people and the governments.

A version of this article was published in Money Control on May 1, 2020. Click here to read

Nila Nair is Research Intern at CPPR-Centre for Comparative Studies. Views expressed by the author are personal and need not reflect or represent the views of Centre for Public Policy Research.