Notification on Vypeen buses

November 29, 2023

Finding Space In The Urban Squeeze: Promise Of Street Vending Zones In Panampilly Nagar

November 30, 2023Elections | How far is India from online ballots?

A decentralised blockchain technology with an immutable ledger could be explored to enhance the security and transparency of voting.

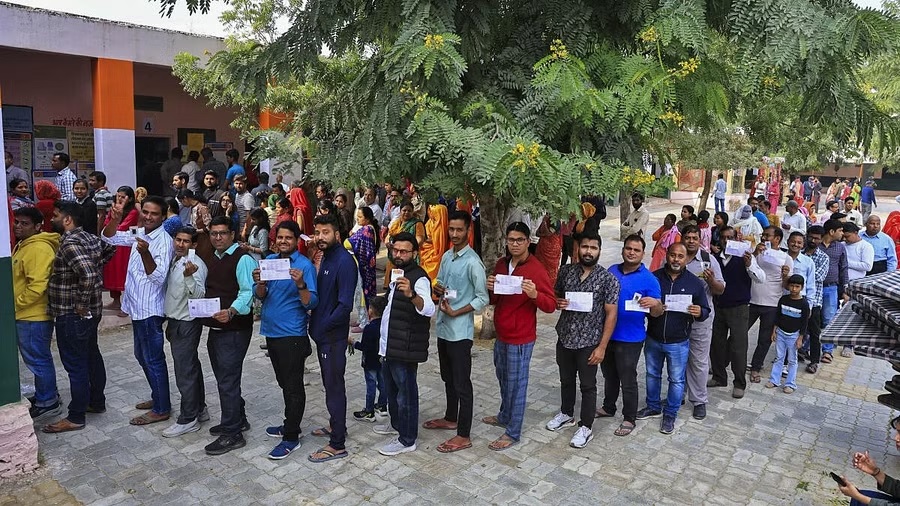

Another set of five assembly elections are concluding this week. As expected, the elections often bring forth discussions around the voter’s turnout, and how various sections of society exercise their rights.

Elections in India are an institutionalised exercise with an active election commission overseeing the proceedings. Over recent decades, the Election Commission of India (ECI) has proactively launched campaigns to boost voter registration and turnout, underscoring its commitment to fostering a robust democratic environment.At the same time, the ECI ensures a fair and unbiased electoral process, upholding the principles of free and open participation for all stakeholders. The advent of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs) has notably elevated the reliability and sophistication of the electoral process in India since the turn of the century.

Yet, the voting percentage in the election varies from place to place. Rural regions in India have consistently exhibited a higher voter turnout than their urban counterparts. In the 2019 elections, the voter turnout in rural areas stood at 69.71 per cent, while the urban turnout was 64.5 per cent. Notably, with 64.5 per cent, cities experienced a surge in voter turnout marking a historic increase. Migration poses a challenge, particularly in the context of voter registration and participation. While migrant voters have the option to register in their new place of residence, the process has not always been seamless. Short-term migrations, in particular, may limit the choice to vote in one’s native constituency.

In response to these challenges, there is a growing demand for the introduction of online voting provisions.The momentum behind this demand often draws parallels with the success of online payment systems and India’s advancements in Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI). While transferring money and participating in the democratic process through voting is fundamentally distinct in philosophy and concept, the ongoing discussion regarding the feasibility of online voting merits attention and exploration.There are many pros and cons cited for online voting. The pros include the possibility of a surge in voter participation by offering the convenience of casting ballots from any location, while also reducing costs associated with transporting, and safeguarding booth materials and the EVMs. Additionally, there’s a potential decrease in logistical expenses.

At the same time, online voting demands high trust and confidentiality, and the building of firewalls around the voting platforms from cyber-attacks, espionage, and the probability of the fraud one can allege. Even decades after introducing EVMs, the ECI has not been able to remove the mistrust and allegations around the process. This takes the experience of online voting in other countries and their learning.Countries such as Estonia, Switzerland, the United States, Canada, Australia, Norway, etc. have introduced online voting mostly in the local elections or allowed those not present locally to vote. Many of these attempts are in the pilot phase and in a minimalistic stage. Amid ongoing debates about the vulnerability of computer networks and concerns about government influence on global online voting platforms, the United Kingdom government, in 2018, declared plans to launch pilots to enhance the acceptance and use of online voting.

What can India do in this context, especially in the context of the growing popularity of the DPI experience?India has the unique advantage of having a robust experience of handling millions of UPI transactions every day. This has led to the clamour for DPI and its advantages. Aadhaar and the widespread use of smart devices are helping this ecosystem grow.The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has introduced two levels of security for the online use of banking cards. A very interesting model India has developed is the One-Time Password (OTP)s linked to mobile numbers, and double verification. Though voting is a totally different exercise and experience, some of these learnings could be applied to test the models. A decentralised blockchain technology with an immutable ledger could be explored to enhance the security and transparency of voting.

There could be a window of opening for the voter for a few minutes to exercise their rights including the verification by using Aadhaar and OTPs. For this, necessary legislation must be brought in.The journey towards widespread adoption of online voting is a gradual one, and immediate confidence in this transition is understandably complex. Safeguarding voters’ rights to cast their ballots securely is currently assured by the structure of present polling stations. However, concerns arise about potential voter intimidation or manipulation when casting votes remotely.Examining the relatively incident-free nature of UPI transactions conducted outside conventional bank branches offers a positive precedent. A similar analogy can be drawn from the experience with postal ballots.

To instil trust incrementally, online voting should undergo pilot phases, commencing with local-level elections. Considering the introduction of a hybrid model in specific regions for testing online voting could serve as a prudent step in this evolving process.

The article was first published on Deccan Herald

(D Dhanuraj is Chairman, and Nissy Solomon is Senior Research Associate, Centre for Public Policy Research)

Views expressed by the author are personal and need not reflect or represent the views of the Centre for Public Policy Research.

Dr Dhanuraj is the Chairman of CPPR. His core areas of expertise are in international relations, urbanisation, urban transport & infrastructure, education, health, livelihood, law, and election analysis. He can be contacted by email at [email protected] or on Twitter @dhanuraj.

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

-

D Dhanuraj

Nissy Solomon is Hon. Trustee (Research & Programs) at CPPR. She has a background in Economics with a master’s degree in Public Policy from the National Law School of India University, Bangalore. After graduation and prior to her venture into the public policy domain, she worked as a Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Analyst with Nokia-Heremaps. Her postgraduate research explored the interface of GIS in Indian healthcare planning. She is broadly interested in Public Policy, Economic Development and Spatial Analysis for policymaking.

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon

-

Nissy Solomon